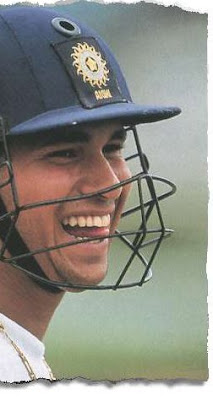

The Berlin Wall was taken down a week before Sachin Tendulka first wore the colours of his country, Nelson Mandela was behind bars, Allan Border was captaining Australia, and India was a patronised country known for its dust, poverty, timid batsmen and not much else. In those days Tendulkar was a tousle-haired cherub prepared to stand his ground against all comers, including Wasim Akram and the most menacing of the Australans, Merv Hughes. Now he is a tousle-haired elder still standing firm, still driving and cutting, still retaining some of the impudence of youth, but nowadays bearing also the sagacity of age.

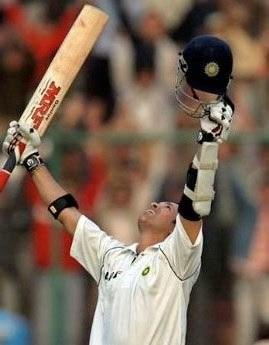

It has been an incredible journey, a trip that figures alone cannot define. Not that the statistics lack weight. To the contrary they are astonishing, almost mind-boggling. Tendulkar has a scored an avalanche of runs, thousands upon thousands of them in every form of the game. He has reached three figures 87 times in the colours of his country, and all the while has somehow retained his freshness, somehow avoided the mechanical, the repetitive and the predictable.

Perhaps that has been part of it, the ability to retain the precious gift of youth. Alongside Shane Warne, the Indian master has been the most satisfying cricketer of his generation.

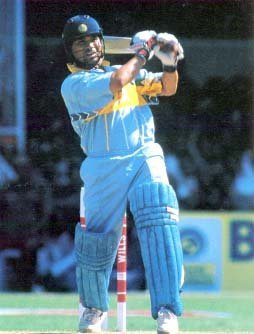

Tendulkar's feats are prodigious. He has scored as many runs overseas as in his backyard, has flogged Brett Lee at his fastest and Shane Warne at his most obtuse, has flourished against swing and cut, prospered in damp and dry. Nor can his record be taken for granted. Batsmen exist primarily to score runs. It is a damnably difficult task made to look easy by a handful of expert practitioners. Others have promised and fallen back, undone by the demands, unable to meet the moment. Tendulkar has kept going, on his toes, seeking runs in his twinkling way.

In part he has lasted so long because there has been so little inner strain. It's hard to think of a player remotely comparable who has spent so little energy conquering himself. Throughout, Tendulkar has been able to concentrate on overcoming his opponents.

But it has not only been about runs. Along the way Tendulkar has provided an unsurpassed blend of the sublime and the precise. In him the technical and the natural sit side by side, friends not enemies, allies deep in conversation. Romantics talk about those early morning trips to Shivaji Park, and the child eager to erect the nets and anxious to bat till someone took his wicket. They want to believe that toil alone can produce that straight drive and a bat so broad that periodically it is measured. But it was not like that.

From the start the lad had an uncanny way of executing his strokes perfectly. His boyhood coaches insist that their role was to ensure that he remained unspoilt. There was no apprenticeship. Tendulkar was born to bat.

Over the decades it has been Tendulkar's rare combination of mastery and boldness that has delighted connoisseurs and crowds alike. More than any other batsman, even Brian Lara, Tendulkar's batting has provoked gasps of admiration. A single withering drive dispatched along the ground, eluding the bowler, placed unerringly between fieldsmen, can provoke wonder even amongst the oldest hands. A solitary square cut is enough to make a spectator's day.

Tendulkar might lose his wicket cheaply but he is incapable of playing an ugly stroke. His defence might have been designed by Christopher Wren. And alongside these muscular orthodoxies could be found ornate flicks through the on-side, glides off his bulky pads that sent tight deliveries dashing on unexpected journeys into the back and beyond. Viv Richards could terrorise an attack with pitiless brutality, Lara could dissect bowlers with surgical and magical strokes, Tendulkar can take an attack apart with towering simplicity.

Nor has Tendulkar ever stooped to dullness or cynicism. Throughout, his wits have remained sharp and originality has been given its due. He has, too, been remarkably constant. In those early appearances, he relished the little improvisations calculated to send bowlers to the madhouse: cheeky strokes that told of ability and nerve. For a time thereafter he put them into the cupboard, not because respectability beckoned or responsibility weighed him down but because they were not required. Shot selection, his very sense of the game, counts amongst his qualities.

On his most recent trip to Australia, though, he decided to restore audacity, cheekily undercutting lifters, directing the ball between fieldsmen, shots the bowlers regarded as beyond the pale. Even in middle age he remains unbroken. Hyderabad confirmed his durability.

And yet, even this, the runs, the majesty, the thrills, does not capture his achievement. Reflect upon his circumstances and then marvel at his feat. Here is a man obliged to put on disguises so that he can move around the streets, a fellow able to drive his cars only in the dead of night for fear or creating a commotion, a father forced to take his family to Iceland on holiday, a person whose entire adult life has been lived in the eye of a storm. Throughout he has been public property, India's proudest possession, a young man and yet also a source of joy for millions, a sportsman and yet, too, an expression of a vast and ever-changing nation. Somehow he has managed to keep the world in its rightful place. Somehow he has raised children who relish his company and tease him about his batting. Whenever he loses his wicket in the 90s, a not uncommon occurrence, his boy asks why he does not "hit a sixer".

Somehow he has emerged with an almost untarnished reputation. Inevitably mistakes have been made. Something about a car, something else about a cricket ball, and suggestions that he had stretched the facts to assist his pal Harbhajan Singh. But then he is no secular saint. It's enough that he is expected to bat better than anyone else. It's hardly fair to ask him to match Mother Teresa as well.

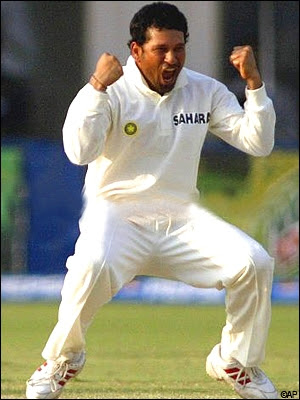

At times India has sprung too quickly to his defence, as if a point made against him was an insult to the nation, as if he were beyond censure. A poor lbw decision- and he has had his allocation- can all too easily be turned into a cause celebre. Happily Tendulkar has always retained his equanimity. He is a sportsman as well as a cricketer. By no means has it been the least of his contributions, and it explains his widespread popularity. Not even Placido Domingo has been given more standing ovations.

And there has been another quality that has sustained him, a trait whose importance cannot be overstated. Not long ago Keith Richards, lead guitarist with the Rolling Stones, was asked how the band had kept going for so long, spent so many decades on the road, made so many records, put up with so much attention. His reply was as simple as it as telling. "We love it," he explained, "we just love playing." And so it has always has been with Tendulkar. It's never been hard for him to play cricket. The hard part will be stopping. But he will take into retirement a mighty record and the knowledge that he has given enormous pleasure to followers of the game wherever it is played.